Today I wrap up these year-end reflections by considering my favourites of the films I saw this year.

I don’t get out to the movies much anymore, so I don’t see movies until they are on DVD. For instance, I’ve seen only a couple of the films on this list of 2016’s best. Instead, I watched a lot of old movies this year, from the likes of Sergio Leone, Howard Hawks, Ingmar Bergman, Satyajit Ray, Krzysztof Kieślowski, François Truffaut, Frank Capra, and Charlie Chaplin. These are all great filmmakers, and no doubt those films were great too, but I’m still learning how to appreciate them, and the films I liked best — the 10 I’ve chosen to discuss in this post — are of recent vintage and generally less distinguished pedigree.

***

By way of prelude: It will come as no surprise that the best film I saw in 2016 was, once again, The Tree of Life. In fact this year I enjoyed it even more than before, in part because I had several opportunities to think about it, both when I wrote about it at Light on Dark Water and when I read Peter Leithart’s book on the film.

But I propose to write today about films I saw for the first time this year.

***

A young Irish woman leaves her family to travel to New York, c.1950, in search of a better future. She slowly makes a life for herself state-side, but then events in Ireland draw her back, and she finds herself torn between two homes, and two competing visions of her future.

A young Irish woman leaves her family to travel to New York, c.1950, in search of a better future. She slowly makes a life for herself state-side, but then events in Ireland draw her back, and she finds herself torn between two homes, and two competing visions of her future.

Yes, of the films I saw for the first time this year, and if plentiful tears are anything to go on, my favourite was Brooklyn. I am a little surprised at this, because unlike some of the films I’m going to praise below, this is pretty much by-the-book movie-making. It has no grand ambitions, no particular sense of style, and no philosophical overtones. But what it does have is a compelling human story and a superb actress in the lead role, and those two elements together carry it through triumphantly. Saoirse Ronan has a quiet but commanding presence, and that Irish lilt is irresistible. (Not since Jennifer Ehle was Elizabeth Bennett have I been so ready to fall in love with a leading lady.) It’s a wonderful performance, and it’s a wonderful film that feels like a classic.

***

My favourite comedy of the year was Whit Stillman’s Love & Friendship. Adapted by Stillman from a little-known novella by Jane Austen, it follows Lady Susan Vernon (played by Stillman regular Kate Beckinsale) as she picks her way through the lives of her circle of friends and relations in the quest to obtain marriages for herself and her grown daughter.

My favourite comedy of the year was Whit Stillman’s Love & Friendship. Adapted by Stillman from a little-known novella by Jane Austen, it follows Lady Susan Vernon (played by Stillman regular Kate Beckinsale) as she picks her way through the lives of her circle of friends and relations in the quest to obtain marriages for herself and her grown daughter.

Lady Susan is a delightful creation: a prodigy of manipulativeness whose capacity for duplicity is boundless and whose conscience is dead. The men in her life, especially — with a notable exception — are helpless before her combination of feminine charms and devious wit. Stillman’s films have all been, to some degree, comedies of manners, so he and Austen are kindred spirits. It feels to me that the period setting, with its latitude for elegant and articulate dialogue, is especially friendly to Stillman’s comedic instincts. Though the film is, at some level, a showcase for guile and hypocrisy, it eventually comes around, as every Austen adaptation must, to a happy ending, and one that feels honest to me. Treachery may have its fascination, but virtue is the charm that most adorns the fair.

Beckinsale dominates the film, but the supporting cast is good. The amiable fool Sir James Martin stands out as a particularly wonderful character; a cheerful idiot whose good intentions leave him ill-prepared to contend against Lady Susan’s wiles; he is played with hilarious volubility by Tom Bennett.

Love & Friendship has its laugh out loud moments, but it’s also a film that has humour in its very bones: in a sense, everything in the film is funny, starting with the title and proceeding through the situations, the characters, the dialogue, and the tone. Even the music, which has been judiciously chosen and carefully integrated into the action, has a comedic role to play. The whole package is highly enjoyable. Decidedly enjoyable. Not unenjoyable at all.

*

My runner-up comedy is 1942’s To Be Or Not To Be, a war-time film about the Nazi invasion of Poland that dared to make the Nazi war machine the subject of farce. One can still sense the dangerous edge of the humour, and apparently the film did offend viewers when first released. But it is easier now to appreciate how well the film is made, to enjoy how delightfully funny it is, and to admire the chutzpah of those who made it.

***

Several films caught my eye this year partly on account of their unusual formal elements.

Dietrich Brüggemann’s searing Kreuzweg (Stations of the Cross), from 2014, follows a young woman preparing for Confirmation in a schismatic Catholic sect. A variety of factors have made life difficult for her, and she wants to offer her suffering to God as a sacrifice for the good of others, but, in this as in so many other matters, teenaged judgment is deficient. Bruggemann structures the whole film around the fourteen traditional Stations of the Cross, and commits to filming each of the stations in one static shot — almost, and that ‘almost’ is key. On one level the film is not really, per se, about this fringe sect, but about the hazards encountered by any group that finds itself positioned against a majority while trying to retain its own intrinsic nature and culture. The issue is not about whether they are right to resist the larger culture — and this film grants the truth of what they believe — but about how difficult it can be, fraught with loneliness and isolation, and fringed with risks of imbalance and fanaticism. It’s a potent film that explores religious faith, friendship, and family life using intentionally minimal means, and it has a terrific ending. (I’ve written at more length about the film at Light on Dark Water.)

Dietrich Brüggemann’s searing Kreuzweg (Stations of the Cross), from 2014, follows a young woman preparing for Confirmation in a schismatic Catholic sect. A variety of factors have made life difficult for her, and she wants to offer her suffering to God as a sacrifice for the good of others, but, in this as in so many other matters, teenaged judgment is deficient. Bruggemann structures the whole film around the fourteen traditional Stations of the Cross, and commits to filming each of the stations in one static shot — almost, and that ‘almost’ is key. On one level the film is not really, per se, about this fringe sect, but about the hazards encountered by any group that finds itself positioned against a majority while trying to retain its own intrinsic nature and culture. The issue is not about whether they are right to resist the larger culture — and this film grants the truth of what they believe — but about how difficult it can be, fraught with loneliness and isolation, and fringed with risks of imbalance and fanaticism. It’s a potent film that explores religious faith, friendship, and family life using intentionally minimal means, and it has a terrific ending. (I’ve written at more length about the film at Light on Dark Water.)

***

Personal sacrifice also plays an important role in La Sapienza (2014), from writer/director Eugène Green, albeit in a different way and with very different results. The film introduces us to Alexandre, a successful architect who, in the midst of honours bestowed upon him, finds he regrets the principles he has followed in his art. He resolves to travel to Italy to study the works of Borromini, the idol of his younger days. His wife, from whom he is very nearly estranged, comes with him initially, but, as it falls out, it is instead a young man, a budding architecture student, who accompanies him to Rome.

Personal sacrifice also plays an important role in La Sapienza (2014), from writer/director Eugène Green, albeit in a different way and with very different results. The film introduces us to Alexandre, a successful architect who, in the midst of honours bestowed upon him, finds he regrets the principles he has followed in his art. He resolves to travel to Italy to study the works of Borromini, the idol of his younger days. His wife, from whom he is very nearly estranged, comes with him initially, but, as it falls out, it is instead a young man, a budding architecture student, who accompanies him to Rome.

Rome! Over the years I’ve tracked down quite a number of films made in the Eternal City simply for the pleasure of watching the backgrounds, but never have I encountered, or even hoped to encounter, a film that puts the city on such loving display as does La Sapienza. The camera fairly caresses the marble facades, and the viewer is invited to bask in the many beauties on display. To call it magnificent is to undersell it.

But the film is more than surfaces: Green, though the adoption of a whole battery of highly unusual conventions in perspective and acting style, asks us to contemplate the depths that surfaces conceal, and to entertain the thought that beauty might be more than just in the eye of the beholder. It is a film that slowly creates around itself a space in which mysterious currents of the spirit flow. It’s rather profound and very lovely, and is unseen, I believe, by almost everyone. (Again, I’ve written a brief essay about it for Light on Dark Water.)

***

As great as are the challenges posed by these last few films, they pale when set beside Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups, a high-wire act of extended cinematic metaphor that, after several viewings, has left me with the sense that I have still only dimly understood it.

As great as are the challenges posed by these last few films, they pale when set beside Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups, a high-wire act of extended cinematic metaphor that, after several viewings, has left me with the sense that I have still only dimly understood it.

The difficulties don’t lie in the basic structure of the film, which is clear enough: we follow Rick, a Hollywood screenwriter, who has lost the thread of his life’s meaning and who must, he faintly recalls, recover it. He lives in forgetfulness, sunk in sensual pleasures and self-gratification, chasing after wind, restless and unsatisfied. It is the story of Pilgrim’s Progress, explicitly so, and our pilgrim must escape life’s hazards and temptations in order to set out for the celestial city.

Many reviewers have said that the film is about the superficiality of Hollywood, but this commits the error of taking literally a film that, it seems to me, takes place almost entirely on an analogical or metaphorical plane. It is about all of us, about the quest which each of us must undertake to shake off our slumber, to leave the pomp and empty promises of the world in order to climb the dry and dusty mountain where God dwells. Hollywood comes into it only because fairy tales work best when the contrasts are bold and consistent, and nothing says pomp and empty promises like Hollywood.

The difficulties of the film lie not in its structure, then, but in its manner. Malick’s recent stylistic hallmarks, following on from To the Wonder, are presented undiluted: almost no on-screen dialogue — and what little there is is often sunk into the mix and made unintelligible — intermittent and often fragmentary voiceover, pervasive symbolism, little conventional acting, discontinuous editing, and — a saving grace — gorgeous cinematography. The images wash over the viewer according to a logic that is often difficult to discern: waves on a shoreline, a city skyline, a road, Rick and one of his (many) girlfriends circling one another, the sun, a swimming pool. It seems to follow a dream logic (and indeed we are told in the first minute of the film that, like Pilgrim’s Progress, it will be “delivered under the similitude of a dream”). This dream aspect allows Malick to mix realism and visual metaphor with gusto. When Rick, at a strip club, crawls into a gilded cage, we understand that a point is being made, and the point is clear. When he stands at a fence gazing at a line of distant palm trees the point may be less evident, until we remember that someone had earlier told him, “You see the palm trees? They tell you anything is possible.” But is this the “possible” of formless self-invention or the authentic “possible” of escaping unreality for reality? Palm trees are trees, tall and thin, which in Malick’s visual vocabulary usually makes them signs of transcendence, reaching instinctively toward the sun.

This call of the transcendent will not leave Rick alone. It seems always present, like the distant roar of the ocean, recalling him to himself especially in his moments of greatest debauchery and aggrandizement. Even when he hears it, however, and even when he heeds it, he faces a recurring question: “How do I begin?” His life’s rotating door for beautiful women testifies to his confusion, for in eros he perceives an intimation of the reality he seeks, though more often than not he mistakes the sign for the reality itself. At one point we hear in voiceover an excerpt from Plato’s Phaedrus, in which feminine beauty is said to remind the soul of the wings which it has lost, evoking in it a desire for flight.

He does eventually begin to recover the thread of his quest, spurred to a significant degree, it seems, by an act of violence that disturbs his restless reverie. He begins to take an interest in meditation, he visits a priest, and, eventually, in one of the more purely metaphorical scenes, he sets foot on the lower slopes of a steep mountain. The resonances with Sinai and Purgatory are very much intended, I expect.

The texture of the film is complex, right down to the sound design. There are moments when there are 3 or even 4 layers of audible “action” occurring at once: on-screen dialogue, interwoven voices of different characters musing to themselves, a narrator, along with music or other sounds. A distinctive feature is that there is almost always a low hum present in the soundtrack; true silence is rare. And this hum is ambiguous, for sometimes it turns out to be the sound of wind or, as I have said, of waves on the shore, but at other times it becomes the sound of a passing car or airplane. It thereby co-operates in one of the film’s leading formal strategies, which is the contrast of the natural world, understood as God’s world, with the textures of modern urban life, the quintessential city of man.

My principal reservations about Knight of Cups pertain to the visual strategy, and in particular to the seemingly disconnected way in which the images sometimes succeed one another. I’ve already conceded that there may be a governing symbolic logic to these sequences, but is the viewer sufficiently tutored in that logic as to able to follow it? A truly great filmmaker should not waste a shot, and while I am convinced that Malick is certainly a great filmmaker, there were moments in Knight of Cups where I was not sure it was a great film, and precisely on these grounds. My jury is still out. The film requires thoughtful attention.

I want to link to two very good essays on the film. At Mubi, Josh Cabrita explores the Christian themes in Malick’s films generally and in Knight of Cups in particular, and at Curator magazine Trevor Logan considers the film from a specifically Kierkegaardian point of view.

***

Successful filmmakers are talented people, and it stands to reason that they might have put those talents to uses other than making movies. Are movies worth committing one’s life to? This is the question explored by the Coen Brothers in Hail, Caesar!, an introspective but witty and appreciative look at the means and ends of movie-making. Set in the Golden Age of Hollywood, it follows a studio executive (Josh Brolin) who has his hands full dealing with the personal foibles of his stars, the intrusive probings of the press, and the many challenges of putting a picture together, all the while pondering an offer to move out of the movie business and into a more practical and respectable line of work. It’s a paen to old-time movies — the Coens take us on set of a number of different productions, but rather than giving us a cursory look they, rather affectionately one feels, let each scene play out in its entirety before moving on — and a good-natured satire on Hollywood too, with bubble-headed big stars in one corner and coteries of Communists hatching dark conspiracies in another. Tonally it’s an odd duck, with farcical elements playing on the surface but serious questions about the value of art underneath. Nevermind, though; the Coens can handle it. Noteworthy are a number of fantastic bit parts played by Scarlet Johanssen, Tilda Swinton, and Ralph Fiennes (whose comic turn as drawing-room drama director Laurence Laurentz is a riot). It’s not quite the greatest story ever told, but it comes closer than you might think.

Successful filmmakers are talented people, and it stands to reason that they might have put those talents to uses other than making movies. Are movies worth committing one’s life to? This is the question explored by the Coen Brothers in Hail, Caesar!, an introspective but witty and appreciative look at the means and ends of movie-making. Set in the Golden Age of Hollywood, it follows a studio executive (Josh Brolin) who has his hands full dealing with the personal foibles of his stars, the intrusive probings of the press, and the many challenges of putting a picture together, all the while pondering an offer to move out of the movie business and into a more practical and respectable line of work. It’s a paen to old-time movies — the Coens take us on set of a number of different productions, but rather than giving us a cursory look they, rather affectionately one feels, let each scene play out in its entirety before moving on — and a good-natured satire on Hollywood too, with bubble-headed big stars in one corner and coteries of Communists hatching dark conspiracies in another. Tonally it’s an odd duck, with farcical elements playing on the surface but serious questions about the value of art underneath. Nevermind, though; the Coens can handle it. Noteworthy are a number of fantastic bit parts played by Scarlet Johanssen, Tilda Swinton, and Ralph Fiennes (whose comic turn as drawing-room drama director Laurence Laurentz is a riot). It’s not quite the greatest story ever told, but it comes closer than you might think.

***

The best horror film I saw this year (from a small sample) was The Witch, the debut of director Robert Eggers. I’ve heard it said that the principal challenge of directing a film lies not so much in the technical aspects, nor specifically in working with the actors and the cameras, but in maintaining a tonal consistency throughout the process, so that the finished product comes to the screen feeling organically put together. Based on this criterion, Eggers is to the manner born. His film rests largely on precisely this careful calibration of tone to generate and maintain suspense. Much of the success of the movie is presumably due to his careful preparation; I understand he gestated this project for several years, doing a great deal of background work to bring the authentic textures of seventeenth-century New England life, including the distinctive cadences of their speech, to the screen.

The best horror film I saw this year (from a small sample) was The Witch, the debut of director Robert Eggers. I’ve heard it said that the principal challenge of directing a film lies not so much in the technical aspects, nor specifically in working with the actors and the cameras, but in maintaining a tonal consistency throughout the process, so that the finished product comes to the screen feeling organically put together. Based on this criterion, Eggers is to the manner born. His film rests largely on precisely this careful calibration of tone to generate and maintain suspense. Much of the success of the movie is presumably due to his careful preparation; I understand he gestated this project for several years, doing a great deal of background work to bring the authentic textures of seventeenth-century New England life, including the distinctive cadences of their speech, to the screen.

The movie, which is subtitled “A New-England Folktale”, is about a Puritan family, banished from their community, trying to establish a new farm in a hard-scrabble wilderness on the edge of a great forest. (The location, in all its glorious desolation, was filmed not all that far from where I live.) They experience a series of strange and increasingly disturbing events that hint at the activity of a malevolent supernatural force dwelling in the forest, and the movie follows them as they do their best to contend against it. It’s a slow movie, heavy on atmosphere and dread, that, at least for most of the runtime, keeps its secrets under wrap.

The film has faults. I have particular reservations about the acting of one of the characters (I shant say which), and, like many people, I have some doubts about the way Eggers chose to end the film. However when first I saw it my principal objection was this: in the world of this movie the power of evil is palpable and effective, but the power of good seems impotent. Prayers for safety and deliverance fall, for all we can tell, into the void, and all the while something definitely not imaginary is encroaching on this family’s peace. This is not only a theological problem, but a dramatic one, for there can be no contest of good and evil if goodness is absent. However when I reflected on the initial setup of the story — that this is not simply depicting a Christian family, but a family that has been cast out from the Church — then in a curious way their impotence before the evil that confronts them might be interpreted as a reaffirmation that extra ecclesiam nulla salus. But this still doesn’t solve the dramatic problem.

***

George Sluizer’s The Vanishing (1988) is a superb psychological thriller about a man whose wife goes missing while they are on holiday. Part of the tension of the film relates to what happened to her, but much of it is focused on the husband left behind. How can he carry on with his life without knowing what become of her? What would he do if she came back? Can he let her go? What would he do to find out what happened to her? At its heart it’s a love story, and a rather convincing one. It is also a study in the psychology of evil, for we spend much of the film observing a third character who is up to no good. Sluizer’s direction is unobtrusive and perhaps a bit flat, though there are a few key shots that use the camera very effectively.

George Sluizer’s The Vanishing (1988) is a superb psychological thriller about a man whose wife goes missing while they are on holiday. Part of the tension of the film relates to what happened to her, but much of it is focused on the husband left behind. How can he carry on with his life without knowing what become of her? What would he do if she came back? Can he let her go? What would he do to find out what happened to her? At its heart it’s a love story, and a rather convincing one. It is also a study in the psychology of evil, for we spend much of the film observing a third character who is up to no good. Sluizer’s direction is unobtrusive and perhaps a bit flat, though there are a few key shots that use the camera very effectively.

The Vanishing is sometimes classified as a horror film. I knew this going in, but was puzzled as I watched, for it didn’t seem to have any horror elements at all. But no: having seen it to the end, it earns its horror film credentials, in spades.

Note that I’m praising here Sluizer’s 1988 Dutch-language film (also called Spoorloos). He re-made the film in English in Hollywood in 1993, but that version I hear is dreadful (and not in a good way).

***

The Hunt is a 2012 Danish film that depicts what happens to a small, closely-knit community when one of its members is accused of a terrible crime. Lucas (Mads Mikkelsen) helps at his village’s kindergarten, but his life becomes a nightmare when he is (wrongly, as we the viewers know from the start) suspected of sexually assaulting one of the children. This is dark subject matter — though not so dark as if the allegations were true — but it nonetheless makes for riveting drama. Friendships rupture, fear and mistrust spread through the community, and Lucas, of course, is ostracized and personally devastated.

The Hunt is a 2012 Danish film that depicts what happens to a small, closely-knit community when one of its members is accused of a terrible crime. Lucas (Mads Mikkelsen) helps at his village’s kindergarten, but his life becomes a nightmare when he is (wrongly, as we the viewers know from the start) suspected of sexually assaulting one of the children. This is dark subject matter — though not so dark as if the allegations were true — but it nonetheless makes for riveting drama. Friendships rupture, fear and mistrust spread through the community, and Lucas, of course, is ostracized and personally devastated.

The film is notable not just for its exploration of personal relationships subjected to intense strain, but for its implicit criticism of well-intentioned “zero tolerance” policies. So much that goes wrong in this village goes wrong because “best practices” are allowed to replace prudential human judgment. Naturally, such policies and practices are intended to promote justice, but The Hunt illustrates how easily the opposite can result.

***

Rounding out my Top 10 is About Elly, from Iranian director Asghar Farhadi. It was originally made in 2009 but only got an international release in 2015, and I caught up with it this year. It’s a stunner.

Rounding out my Top 10 is About Elly, from Iranian director Asghar Farhadi. It was originally made in 2009 but only got an international release in 2015, and I caught up with it this year. It’s a stunner.

The story is about a group of families who go together to a beach-house for the weekend. One of the families invites their child’s teacher, Elly, to come along as a guest. The first half of the film is a loose study of how this group of people interact with one another, how certain personalities dominate, what they think of one another, and how they include or subtly exclude their guest. With deft use of foreground and background and reliance on multiple overlapping conversations it feels like a Robert Altman masterclass, while also preparing us for the film’s crucial sequence.

In that sequence, which occurs at about the mid-point, something happens (which I’ll not reveal); when it is over Elly is gone and no-one is sure where. The second half of the film is then a drama exploring how all of those relationships we learned about in the first half change under stress. We are shown the devastating power of lies, and the film finally arrives at a point where the duty to tell the truth is surpassingly clear and pressing. It’s a terrific movie.

***

Brief thoughts on other films

Apart from the few runners-up already indicated, I also enjoyed this year the CGI-animated The Jungle Book, though it’ll not replace the 1967 film in my affections, and the documentary The Look of Silence, a follow-up to The Act of Killing from Joshua Oppenheimer, a man with a fair claim to be the world’s bravest filmmaker. I saw Spotlight, Best Picture winner at the 2016 Oscars, and while I thought it was quite good, and appreciated its willingness to tell its story clearly and soberly, it wasn’t as good as its model, All the President’s Men (1976), which I also saw this year. Other highlights for me were the harrowing escape drama Green Room, with Patrick Stewart a superb villain, and the off-beat but delightful Bird People, about … bird people.

*

In the waning days of the year I was unexpectedly able to see Terrence Malick’s Voyage of Time. This film has been released in two versions: a 90-minute version for regular theatres and a 40-minute version for IMAX theatres. It was the latter that I saw, at our local science centre, with two of my kids and a crowd of holidaying families. This was a bit like going to Disneyland and finding an exhibition of Rembrandt and Titian. My guess is that few of those present were expecting this contemplative, philosophical pondering of what natural history tells us about the universe and ourselves. Malick wonders about the origin of being, about whether consciousness preexists created minds, and whether it is love that animates and unites the natural order. The film is visually stunning — imagine a longer version of the creation sequence in The Tree of Life — and the music, dominated by Mahler 2, Arvo Pärt, and the Mass in B Minor, is superb.

I loved it. I must say, too, that I was proud of my kids (5yo and 7yo), who were fully engaged with it throughout. Eldest Daughter’s favourite part was a quiet moment in which the camera floated gently down a stream between high canyon walls — a lovely moment, to be sure — and Eldest Son’s favourite part was the space shuttle launch — in truth, this was part of the pre-film demonstration of the IMAX theatre’s sound system, but he did very well. Now, if only I could see the longer version…

*

Did you see Peter Jackson’s Hobbit films? I suffered through the first two but dodged the third. But this year I learned that an enterprising fan had edited the trilogy to exclude anything not in the book, which cuts the run-time in half. This Tolkien Edit I did see, and while I would not quite call it good, it was decently enjoyable, and certainly far superior to the theatrical versions.

***

Miscellanea

Oldest films: Dante’s Inferno (1911); Safety Last! (1923); The Thief of Bagdad (1924)

Newest films: Voyage of Time: IMAX (October); The Conjuring 2 (June); The Jungle Book (April)

Most films by the same director(s): 4 (Coen Brothers & Terrence Malick)

Longest films: The Right Stuff (1983) [3h13m]; Magnolia (1999) [3h08m]; Fanny and Alexander (1982) [3h08m]

Shortest films: World of Tomorrow (2015) [0h17m]; Night and Fog (1955) [0h32m]; Voyage of Time: IMAX (2016) [0h40m]

Started, but not finished: Dazed and Confused (1993), The Peanuts Movie (2015)

Disappointments: Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), Safe (1995), The Right Stuff (1983)

Films I failed to understand: Werckmeister Harmonies (2000); La double vie de Véronique (1991)

Most egregious foregrounding of bad music: Sing Street (2016)

Best hagiography: Jean la Pucelle (1994)

Scariest goat: The Witch (2015)

***

And that, more or less, was my year in movies. Comments welcome!

gun a habit of reading a Shakespeare play every month, and I continued that practice this year, with much enjoyment. Inspired by the BBC series

gun a habit of reading a Shakespeare play every month, and I continued that practice this year, with much enjoyment. Inspired by the BBC series  By way of compensation, perhaps, I read one of the classics of Shakespearean criticism in Samuel Johnson’s

By way of compensation, perhaps, I read one of the classics of Shakespearean criticism in Samuel Johnson’s  As usual, classical and medieval texts were important to me this year, and I’ve just mentioned a few of them. I re-read Plato’s Protagoras during summer vacation; this is a dialogue that I’ve admired for years, partly for the comical description Socrates gives us of the titular sophist and his acolytes, but mostly for an exchange early in the dialogue in which Socrates counsels young Hippocrates to be careful about what influences he exposes his soul to, for the soul, after all, is not a shopping basket from which items can be removed as easily as added; this good counsel I have long taken to heart in my own conduct, or at least I hope I have. Also, since it had been some years since I read Aristotle, this year I tackled the Politics, and, to my considerable surprise, found it rather tedious. There were some good bits, to be sure, especially in Book VIII, which treats education, but for the most part it went deeper into the policy weeds than I cared to go.

As usual, classical and medieval texts were important to me this year, and I’ve just mentioned a few of them. I re-read Plato’s Protagoras during summer vacation; this is a dialogue that I’ve admired for years, partly for the comical description Socrates gives us of the titular sophist and his acolytes, but mostly for an exchange early in the dialogue in which Socrates counsels young Hippocrates to be careful about what influences he exposes his soul to, for the soul, after all, is not a shopping basket from which items can be removed as easily as added; this good counsel I have long taken to heart in my own conduct, or at least I hope I have. Also, since it had been some years since I read Aristotle, this year I tackled the Politics, and, to my considerable surprise, found it rather tedious. There were some good bits, to be sure, especially in Book VIII, which treats education, but for the most part it went deeper into the policy weeds than I cared to go. As an adjunct to this Begegnung with Heidegger, I watched a brace of Terrence Malick’s films, and as an adjunct to those I read Peter Leithart’s

As an adjunct to this Begegnung with Heidegger, I watched a brace of Terrence Malick’s films, and as an adjunct to those I read Peter Leithart’s  fluency, but O’Brian’s ear for authentic nineteenth-century English is unerring; never does one experience the jarring anachronisms that ambush less able authors of historical fiction. As for Wodehouse, I’ve been prancing my way through the Jeeves and Wooster books, and enjoying every ridiculous minute of it. Wodehouse’s stories are froth, but effervescent froth, and his prose cannot be improved. The long-form stories (rather than the single-chapter short stories) have made the strongest appeal to me, and my favourites thus far have been The Code of the Woosters and Joy in the Morning. Wodehouse wrote about 100 books, so this reading project is going to continue for the foreseeable future.

fluency, but O’Brian’s ear for authentic nineteenth-century English is unerring; never does one experience the jarring anachronisms that ambush less able authors of historical fiction. As for Wodehouse, I’ve been prancing my way through the Jeeves and Wooster books, and enjoying every ridiculous minute of it. Wodehouse’s stories are froth, but effervescent froth, and his prose cannot be improved. The long-form stories (rather than the single-chapter short stories) have made the strongest appeal to me, and my favourites thus far have been The Code of the Woosters and Joy in the Morning. Wodehouse wrote about 100 books, so this reading project is going to continue for the foreseeable future.

With our eldest, now seven, we spent most of the year on chapter books, and the best of them were George MacDonald’s atmospheric fantasy

With our eldest, now seven, we spent most of the year on chapter books, and the best of them were George MacDonald’s atmospheric fantasy

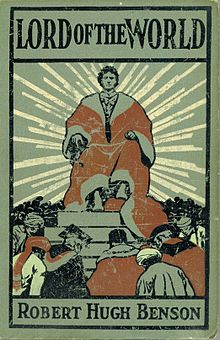

Lord of the World

Lord of the World