My music listening this year was anchored by a few large listening projects: I marked the anniversary years of Verdi, Wagner, and Britten by dedicating a good deal of time to hearing their major works again — or, in some cases, for the first time. Given the composers involved, much of this music was opera, and I tried when possible to watch performances of their operas on DVD. I’ve written about some of that music in the consistently unpopular “Great moments in opera” series that I’ve been running (and a few more anniversary-related instalments will trickle out over the next month or two).

I had planned a bunch of other focused listening projects for the year too — Beethoven’s symphonies, Shostakovich’s symphonies and string quartets, Schubert’s piano sonatas — but I didn’t get to them. They are bumped to 2014.

In the meantime, I’d like to share notes on a few of the best recordings I heard for the first time this year. In most cases these are new or new-ish recordings, but not in all. The predominance of vocal music reflects my interests. The ordering of this list is capricious.

Weinberg: Complete Violin Sonatas

Weinberg: Complete Violin Sonatas

Linus Roth, Jose Gallardo

(Challenge, 2013)

For the last few years music of Mieczyslaw Weinberg has figured in my year-end accolades, and the same is true this year. This three-disc set is the first complete recorded set of Weinberg’s music for violin and piano, and what a treasure it is! Weinberg wrote six very substantial violin sonatas that exhibit the same musical intelligence and emotional heft that I have admired in his string quartets. As I said of the quartets, this music is “music all the way down”: no pedantry, no gimmicks, no self-conscious preoccupation with the music or its manner of composition — just good, smart, heart-felt music that is full of variety and endlessly interesting. I am happy to see Weinberg’s star rising higher on the strength of recordings like this one. Move over, Prokofiev.

Here is a brief video with musical excerpts and interviews with the musicians:

Elgar: The Apostles

Halle Orchestra, Sir Mark Elder

(Halle, 2012)

This recording of Elgar’s oratorio about the life of Christ, from the calling of the apostles to the Ascension, won BBC Music Magazine’s “Recording of the Year”; there may have been some Anglo-centric prejudice informing that decision, but this is a terrific performance of a piece that hasn’t been very well served on record (and which, I suspect, might not finally be top-shelf music). The great fear with Elgar is that amateur British choral societies are going to get their hands on him, serving up bloated and sentimental renditions of his music before the potluck. It is amazing to hear this music sung as crisply and clearly as it is here, with a cool glow and as much dramatic emphasis as the music can bear without buckling. The singing is really tremendous, especially in the choral sections, and the sound is as clear and vivid as one could hope for. This recording has made me reconsider the merits of this piece, and made the reconsideration a pleasure. [Listen to excerpts]

Wagner

Wagner

Jonas Kaufmann

Orchester der Deutschen Oper Berlin, Donald Runnicles

(Decca, 2013)

Jonas Kaufmann, who glowers from the front cover of this CD, is considered one of the leading tenors in the opera world today, and he really is prodigiously gifted: a magnificent voice that rings from top to bottom, great power, and keen dramatic instincts. It is this last that has most impressed me on this disc of Wagner extracts. For all that Wagner was undoubtedly a great composer, it has nevertheless often seemed to me that his genius was principally manifest in his orchestral writing, and that his vocal lines were largely meandering eddies floating atop the surging currents, lacking dramatic shape and melodic interest in themselves. I won’t say that this recording has changed my opinion about his melodic gifts, but it has certainly made me reconsider my assessment of the dramatic shape of his writing. Never before have I heard Wagner sung in a way that brought out the taut dramatic energy, the sheer poise and responsiveness of the part as much as Kaufmann does. He has helped me to hear Wagner with new appreciation, and that is enough to get this recording onto this list.

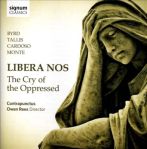

Libera Nos: The Cry of the Oppressed

Contrapunctus, Owen Rees

(Signum, 2013)

The programme on this CD is a well-conceived one, gathering together a number of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century choral works on the themes of oppression and liberation by English and Portuguese composers. English Catholics in this period suffered persecution by the authorities, and Portugal was under the domination of the Spanish monarchy. Composers turned to these (mostly) liturgical texts to express their prayers for deliverance with a degree of personal feeling that is rare in public ecclesiastical music. The music is breathtakingly beautiful, of course, and the singing on this recording is very distinguished. Contrapunctus is a British choir formed in 2010; this is their first recording. They are a small ensemble of about ten voices, men and women, and they sing with astounding clarity and beauty; I don’t hear any problems anywhere. The multi-layered harmonic and rhythmic complexity of these pieces comes across sounding effortless (which it certainly is not) and, what is more important for this particular programme, there is nothing impersonal about the singing: it has a plaintive, striving quality that suits these pieces very well. Top shelf. [Listen to excerpts]

Ockeghem: Missa Mi-Mi

Ockeghem: Missa Mi-Mi

Cappella Pratensis, Rebecca Stewart

(Ricercar, 1999)

It was a year or two ago that I discovered the Dutch ensemble Cappella Pratensis. I liked them well enough to go searching through their back catalogue, and in this recording of Johannes Ockeghem’s Missa Mi-Mi I found a real gem. This Mass is one of Ockeghem’s most frequently recorded, and I have heard it many times, but never with this degree of translucence and calm repose. I tend to bristle at the common view that the music of this period is “relaxing” or “peaceful”, as though these frequently very difficult, intricate, and rigourously structured compositions were merely a kind of soporific. Yet in this case there would be something to that rough characterization, for this ensemble finds in this music a spaciousness and gentleness that lifts the eyes and touches the heart in a quite special way. The music breathes in long, slow rhythms, unhurried, as though content, at each moment, simply to be an expression of praise and a profusion of beauty. I don’t know that I’ve ever heard Ockeghem sung in this way before; I don’t know that I ever will again. The Mass is presented in a quasi-liturgical context, embedded within the Propers for the Mass of Holy Thursday, and the programme ends with Ockeghem’s magnificent motet Intemerata Dei mater.

Here is the Kyrie of the Missa Mi-Mi:

Bach: Cantatas, Vol.55

Bach Collegium Japan, Masaaki Suzuki

(BIS, 2013)

This disc is on this list not so much for its own merits — although it is exceptionally good — but for what it represents: the completion of Masaaki Suzuki and Bach Collegium Japan’s twenty-years-long project to record all of Bach’s surviving cantatas. Should I be ashamed to admit that I have collected all fifty-five volumes? Maybe so, but think of all the beer I didn’t buy. Japan might not be the country we think of first when we think of Bach (quite wrongly, perhaps), but the proof is in the pudding: the performances on this disc and across the whole set have been consistently excellent. Suzuki’s approach to the music is “historically informed”, which means in practice that the choir is small and lithe, the textures light, and the rhythms sprightly. It’s Bach played and sung just the way I like it. Here is the Bach Collegium Japan performing one of the cantatas on this final disc. Bravo!

Whitacre: Sainte-Chapelle

Whitacre: Sainte-Chapelle

Tallis Scholars

(Gimell, 2013)

Eric Whitacre is one of the more successful young composers working today. As far as I know, he writes mostly choral music, in an accessible idiom within the reach of amateur choirs, and quite a few recordings of his music are now available. He was commissioned by the Tallis Scholars to write a piece to celebrate the 40th anniversary of their founding, and he came up with Sainte-Chapelle, a piece which imagines the stained-glass angels in that beautiful church singing the Sanctus. The piece was premiered early in 2013 and recorded shortly thereafter. It must be said that it is a gorgeous piece, growing in energy and luminosity as it goes. I had never before heard the Tallis Scholars sing anything other than Renaissance polyphony, but Whitacre’s writing respects their area of specialization, growing out a plainchant melody just as so many Renaissance pieces do. I’ve played this recording so frequently this year that I cannot but include it on this year-end list.

***

Honourable mentions:

Ludford: Missa Regnum mundi

Ludford: Missa Regnum mundi

Blue Heron

(Blue Heron, 2012)

[Watch] [Listen]

Schubert: Nacht und Traume

Schubert: Nacht und Traume

Matthias Goerne, Alexander Schmalcz

(Harmonia Mundi, 2011)

[Listen]

Howells: Requiem

Howells: Requiem

Choir of Trinity College, Cambridge; Stephen Layton

(Hyperion, 2012)

[Watch] [Listen]

Yoffe: Song of Songs

Yoffe: Song of Songs

Rosamunde Quartett, Hilliard Ensemble

(ECM New Series, 2011)

[Listen]

Victoria: Officium Defunctorum

Victoria: Officium Defunctorum

Collegium Vocale Gent, Philippe Herreweghe

(Phi, 2013)

[Listen]

Mahler: Symphony No.2 “Resurrection”

Mahler: Symphony No.2 “Resurrection”

Sarah Connolly, Miah Persson

Philharmonia Orchestra, Benjamin Zander

(Linn, 2013)

[Listen]

Praetorius: Advent and Christmas Music

Praetorius: Advent and Christmas Music

Bremer Barock Consort, Manfred Cordes

(CPO, 2007)