I had a rewarding year watching movies in 2018, somehow managing to cram quite a few into the nooks and crannies of my works and days. For this year-end list I’ve chosen ten of my favourites. Since they all have something to recommend them, I have not ranked them, but simply listed them in alphabetical order.

***

Paul Schrader is best known as a screenwriter for Martin Scorcese (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull), and is also the author of a minor classic of film criticism in Transcendental Style in Film. These strands, and others, including his Reformed Christian upbringing, come together in First Reformed (2017), which he both wrote and directed. A middle-aged clergyman, played with weary sympathy by Ethan Hawke, presides over an historic, but moribund, Dutch Reformed parish. His congregation is so small that First Reformed’s day-to-day operations, including Reverend Toller’s own income, are paid for by Abundant Life, a friendly evangelical mega-church down the road. First Reformed is preparing to celebrate its 250th anniversary, and Toller is beset by troubles, both personal and political.

Paul Schrader is best known as a screenwriter for Martin Scorcese (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull), and is also the author of a minor classic of film criticism in Transcendental Style in Film. These strands, and others, including his Reformed Christian upbringing, come together in First Reformed (2017), which he both wrote and directed. A middle-aged clergyman, played with weary sympathy by Ethan Hawke, presides over an historic, but moribund, Dutch Reformed parish. His congregation is so small that First Reformed’s day-to-day operations, including Reverend Toller’s own income, are paid for by Abundant Life, a friendly evangelical mega-church down the road. First Reformed is preparing to celebrate its 250th anniversary, and Toller is beset by troubles, both personal and political.

Schrader has said that the film is his tribute to a number of his best loved filmmakers, and one can catch the influence of Bergman and especially Bresson, whose country priest is never far away. It is a beautifully filmed and carefully put together picture. Like Taxi Driver, it takes a wild turn in the final act, so wild that it will confound many viewers; I was very nearly among them. But on reflection I lean toward admiration of the film’s boldness. Even if it is not believable as a realistic story, it works as a fable, and that fable is about — what? Maybe simply the hazards of our need for meaning; or the temptation to see politics as a substitute for faith; or, though it seems a cliché, the power of love to overcome violence and despair. It’s a complex, artfully constructed film, very much worth seeing.

*

The first and maybe best reason to see Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty (2013) is that no other film shows Rome to better effect. To see the city filmed with such sumptuous beauty — and magically empty of tourists! — was a glorious consolation to me.

The first and maybe best reason to see Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty (2013) is that no other film shows Rome to better effect. To see the city filmed with such sumptuous beauty — and magically empty of tourists! — was a glorious consolation to me.

And that might well be the only consolation on offer. Jep — Jeppino, as he is once called, and fittingly — is a Roman socialite, one-time novelist, living off the fumes of his literary reputation and enjoying his posh creature comforts. Having reached his 65th birthday, he begins to take stock of himself, and, rightly, finds himself wanting. The film alternates between bacchanales and quiet, ruminative moments as Jep ponders how his life, and he himself, might acquire more weight and substance. He considers a variety of remedies: popularity, artistic creation, religion, sex, love. All, with the possible exception of some combination of the latter two, the film rejects with greater or lesser degrees of smugness. It is, in this sense, a spiritually dark film, blind to certain possibilities. An instinctive cynicism, which reveals itself most clearly in the film’s gorgeous opening sequence, is its chief defect.

Jep says he is lost because he was looking for the great beauty, but never found it. But were you really, Jep? Be honest.

Despite my misgivings, it is a film that grapples with a serious matter — the search for meaning in a world bereft of transcendence — and for this I honour it. That is seems to have nothing to say in the end is, first, honest, for there is no good answer given those premises, and, second, belied by the manner in which it is presented: saturated with a beauty that just might undermine the complacent immanence of Jep’s world. The film may be wiser than it seems at first blush.

*

At the beginning of Loveless (2017) a young boy goes missing; he is an only child, and his parents are in the throes of a separation. The police are called; search parties are formed; the boy must be found.

At the beginning of Loveless (2017) a young boy goes missing; he is an only child, and his parents are in the throes of a separation. The police are called; search parties are formed; the boy must be found.

Except that the film cannot keep its mind on the plot. Instead it lures us into the self-involved, oh-so-understandable troubles of the boy’s parents, adults who have things on their minds, new lovers, and what they would no doubt call emotional needs. They are petty and selfish, and we, to the extent that we are drawn into their concerns, are subject to the same damning criticism. Not often have I felt so strongly that a film, as I watched it, was watching me with an unsparing eye.

There is wonderful art here: patient direction, fantastic lighting and cinematography, creative use of the camera. Like the director’s previous film, Leviathan, it moves slowly but surely. What I appreciated most was its withering, steely-eyed interrogation of that mother and that father. Here, friends, is a film about divorce that is cold as ice and entertains no excuses.

*

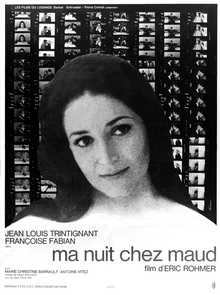

Ma Nuit chez Maud (1969), one of Eric Rohmer’s ‘Moral Tales’, is a closely observed study of the gap between ideals and actions, and of the difficulty of knowing the heart, whether our own or another’s. We follow Jean-Louis — a thirty-something man, articulate, somewhat lonely, a committed Catholic — who is invited by a friend to the home of Maud, a beautiful young divorcée. When the friend departs, Jean-Louis is left alone with Maud, and a long conversation, like a dance, begins, as she gently but persistently probes his integrity, and he, more brusquely and instinctively, hers.

Ma Nuit chez Maud (1969), one of Eric Rohmer’s ‘Moral Tales’, is a closely observed study of the gap between ideals and actions, and of the difficulty of knowing the heart, whether our own or another’s. We follow Jean-Louis — a thirty-something man, articulate, somewhat lonely, a committed Catholic — who is invited by a friend to the home of Maud, a beautiful young divorcée. When the friend departs, Jean-Louis is left alone with Maud, and a long conversation, like a dance, begins, as she gently but persistently probes his integrity, and he, more brusquely and instinctively, hers.

Their encounter works on a metaphorical level — this was 1969, after all, and in that room we see the sexual revolution coming up against the Catholic order of marriage and sexuality, which, if nothing else, makes the film a fascinating cultural artifact — but it also works, and works quite beautifully, on a personal level, as a tale about two people who, though very different, find one another strangely fascinating. The film has a second act in which Jean-Louis falls in love with a Catholic woman; this section reconnects with the first in some surprising ways that reinterpret what we have seen before while reiterating and deepening the film’s main concerns. Altogether an excellent film.

*

I haven’t seen many film noir on par with Out of the Past (1947). Robert Mitchum plays a man trying to start again, but his past life of crime will not let him be, and he is forced back into that world in a final effort to escape. Mitchum is weary, imperturbable, and sometimes inscrutable, such that when the plot warms up we cannot be entirely sure his crossings are not double-crossings. Much the same could be said of the excellent femme fatale character, played by Jane Greer. It’s a film in which the men are as tough as you’d expect, the women are as beautiful as you’d hope, but people aren’t always who and what they seem to be.

I haven’t seen many film noir on par with Out of the Past (1947). Robert Mitchum plays a man trying to start again, but his past life of crime will not let him be, and he is forced back into that world in a final effort to escape. Mitchum is weary, imperturbable, and sometimes inscrutable, such that when the plot warms up we cannot be entirely sure his crossings are not double-crossings. Much the same could be said of the excellent femme fatale character, played by Jane Greer. It’s a film in which the men are as tough as you’d expect, the women are as beautiful as you’d hope, but people aren’t always who and what they seem to be.

Dialogue in film noir is often darkly witty, but I can’t think of a single film that surpasses this one in that respect. (Roger Ebert’s review gives some examples, and they could be multiplied.) The director is Jacques Tourneur, who also made Cat People, a superior film of the creepy sort. In any case, with an abundance of trench-coats and cigarettes, and style to burn, Out of the Past is highly recommendable.

*

In the contest for least-inspired movie title, one could hardly do better, or rather worse, than Personal Shopper (2016), but that blandness is a disservice to an involving film that never does what we expect, becomes more puzzling and fascinating as it proceeds, and concludes by increasing rather than resolving the tension it generates. The film is centred on Maureen, an American living in Paris, who is mourning the recent death of her brother, and, more than just mourning, is waiting for him to send her a sign from beyond the grave. He had been a medium of some talent, and Maureen believes that she has this gift too. And she does have experiences that could be, perhaps, signs, but are hard to interpret. The film gradually — too gradually for some, perhaps — builds toward a crisis in which something very dramatic occurs, although just what is hard to say. Like those messages Maureen seeks, the film, too, is hard to interpret.

In the contest for least-inspired movie title, one could hardly do better, or rather worse, than Personal Shopper (2016), but that blandness is a disservice to an involving film that never does what we expect, becomes more puzzling and fascinating as it proceeds, and concludes by increasing rather than resolving the tension it generates. The film is centred on Maureen, an American living in Paris, who is mourning the recent death of her brother, and, more than just mourning, is waiting for him to send her a sign from beyond the grave. He had been a medium of some talent, and Maureen believes that she has this gift too. And she does have experiences that could be, perhaps, signs, but are hard to interpret. The film gradually — too gradually for some, perhaps — builds toward a crisis in which something very dramatic occurs, although just what is hard to say. Like those messages Maureen seeks, the film, too, is hard to interpret.

I watched Personal Shopper twice this year, separated by several months, because I wanted to give my first enthusiasm for it a chance to wane before another sober viewing. On second acquaintance I am less convinced it holds together. Most vexing is that there does not seem to be any one interpretation of the film’s final half-hour that makes sense of all we are shown. Nonetheless, the film’s quiet exploration of desire and loneliness, underpinned by an excellent low-key performance by Kristen Stewart in the lead role, coupled with intriguing plot developments that had me watching and re-watching certain scenes with great attention, made it for me one of the more fascinating film experiences of the year.

*

It has been a decade since a Paul Thomas Anderson film won my admiration, but Phantom Thread (2017) did the trick. Anderson seems to have gradually left behind the Dionysian freedom of his early films in favour of something more controlled and subdued, and Phantom Thread is positively Apollonian in construction, classic in every respect, from its elegant camera work to its beautiful sets and costumes and masterclass acting. Within that graceful framework, however, he has given us a pretty bizarre tale.

It has been a decade since a Paul Thomas Anderson film won my admiration, but Phantom Thread (2017) did the trick. Anderson seems to have gradually left behind the Dionysian freedom of his early films in favour of something more controlled and subdued, and Phantom Thread is positively Apollonian in construction, classic in every respect, from its elegant camera work to its beautiful sets and costumes and masterclass acting. Within that graceful framework, however, he has given us a pretty bizarre tale.

The story is that of an artist — Reynolds Woodcock, a dress designer in London in the 1950s — and his muse, Alma, a younger woman whom he meets when she waits on his table one morning in a hotel. Reynolds has been through this before, typically retaining his young women until their value as a muse wears off. But Alma is different; initially overwhelmed by the glamour of the life into which she has been spirited, she cannily finds a way to make a place for herself. The film is very much a study of the complicated relationship that develops between these two.

Thus far the story sounds like one we’ve heard before, more or less, but Anderson has a way of taking his films where we do not expect them to go, and the final act of Phantom Thread strays well outside established conventions. Anderson has prepared the ground quite carefully, but subtly enough that I missed it on first viewing. As the film drew to a close I actually began to wonder — if you know PTA’s other films — whether Alma was going to drink a milkshake.

If the terminus of the story arc sits rather uncomfortably on my mind, the rest of Phantom Thread is of the purest and most luxuriant filmcraft. Daniel Day-Lewis, who gave one of the greatest film performances known to me in Anderson’s There Will Be Blood, gives a very different but, I am tempted to say, comparably impressive performance as Woodcock, a man of fastidious habits and sensitive temper into whom Day-Lewis disappears. That Vicky Krieps, as Alma, can hold the screen with him is high praise. There is a delightful vein of understated humour running through the film that adds sparkle, and everything about the production and direction is the work of a master.

*

I saw two good films this year with titles beginning A Quiet P. One was the thrilling blockbuster sci-fi alien invasion disability farm family pregnancy drama A Quiet Place, which caused me to carefully check all the staircases in my house for a particular hazard. The other was A Quiet Passion (2016), about an unlikely cinematic subject: Emily Dickinson.

I saw two good films this year with titles beginning A Quiet P. One was the thrilling blockbuster sci-fi alien invasion disability farm family pregnancy drama A Quiet Place, which caused me to carefully check all the staircases in my house for a particular hazard. The other was A Quiet Passion (2016), about an unlikely cinematic subject: Emily Dickinson.

To make a film on the life of a poet seems a daunting challenge; the cinematic potential of a woman sitting at a desk, pen in hand, are limited. But of course Emily Dickinson was a woman like other women, with a family, and views on religion and society, and the dramatic possibilities to be drawn from a network of close relationships between articulate speakers gathered in a sitting room are, as we have learned from Jane Austen, rich and delightful, and A Quiet Passion makes much of its slender material.

(Speaking of Austen, by a peculiarity of the casting — in particular, by having Jennifer Ehle play the handsome second sister — I was continually tempted to conflate this story with the famous Pride and Prejudice adaptation! In this parallel universe, our poet appears in the role of Jane, the slightly homely, taller, thinner sister who has a harder time in social circles. Never had I suspected that Jane was a poet! Sadly Mr Darcy makes no appearance, having drowned, perhaps, in the pond.)

The oddest thing about A Quiet Passion is the dialogue. In the first half or two-thirds, dialogue consisted largely of aphorisms, as though everybody was choosing lines from an Oscar Wilde anthology. Quite stagey. Strangely, this effect seemed to dwindle as the film progressed.

As much as I enjoyed the story, and I did, for me the principal attraction of this film was the direction. It is my first Terence Davies film, and I am now very interested in seeing others. The direction is careful, with slow pans and beautiful compositions, and transitions are managed elegantly. I had the impression that Davies is a superb craftsman.

*

Every year since 2011 I have named Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011) as my favourite film of the year. (Readers interested in why I love it might read this.) This year I watched it again, of course, but with a difference: a new, extended version of the film was released. The extended version adds about 45 minutes to the original 140 minutes, so it is a substantial augmentation.

Every year since 2011 I have named Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011) as my favourite film of the year. (Readers interested in why I love it might read this.) This year I watched it again, of course, but with a difference: a new, extended version of the film was released. The extended version adds about 45 minutes to the original 140 minutes, so it is a substantial augmentation.

Most sections of the film have been altered to some extent, sometimes just by brief insert shots. The most substantial changes are twofold: first, to the scenes with the adult Jack (Sean Penn), which are fleshed out and expanded from the modest material in the original version, and, second, to the long central section of the film devoted to life in the O’Brien’s household. To this section, which has always been the heart of the film, new story elements are introduced, including a dramatic storm sequence, and a new and quite upsetting plot development. The overall effect is to enrich the portrait of this family, deepening our appreciation of them. By giving this (fairly) traditionally narrative section of the film more weight, the new film has its feet planted more firmly on the ground than did the earlier, more enigmatic version. Something is gained, but also lost. And the new version clocks in at more than three hours; I don’t know how it is where you live, but for me it is hard to find three uninterrupted hours to do anything.

So, in the end, I’m not sure which version I prefer. My resolution, for future viewings, is to alternate until such time as one version wins my heart. In the meantime, The Tree of Life, Extended Version was my favourite film of the year.

*

The joys and pitfalls of young love are the theme of Jacques Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Shot in retro black and white, it tells the story of two young French lovers whose romance is interrupted by war but nonetheless continues to overshadow their lives. It is a beautiful but bittersweet film that just might break your heart in the end. Part of its beauty is its special conceit: it is entirely sung. There are no ‘big numbers’, just a steady stream of through-composed music that floats the film from its first scene to its last, with the singing a kind of heightened speech. Be careful, though: your jazz allergy may act up.

The joys and pitfalls of young love are the theme of Jacques Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Shot in retro black and white, it tells the story of two young French lovers whose romance is interrupted by war but nonetheless continues to overshadow their lives. It is a beautiful but bittersweet film that just might break your heart in the end. Part of its beauty is its special conceit: it is entirely sung. There are no ‘big numbers’, just a steady stream of through-composed music that floats the film from its first scene to its last, with the singing a kind of heightened speech. Be careful, though: your jazz allergy may act up.

**

I have listed ten films. Most were easy to choose; a few were difficult on account of competition from other good films. Those that missed my list this year, and might have made it were my mood swings more erratic, were The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018), La Fille inconnue (2016), Paper Moon (1973), and Top Hat (1935).

***

Best superhero film: Wonder Woman (2017), the greatest wonder of which was that it included a battle between two invincible characters that was not dull as dirt.

Best action film: American Made (2017), if it is properly called an action film.

Best musical: The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964).

Best animated: The Hobbit (1977), a weirdly folkadelic take on Tolkien’s tale that nonetheless managed to capture some of the childlike spirit of the book.

Best filmed stage performance: Romeo and Juliet, from the Globe Theatre; the best production of this play that I have seen, for stage or screen.

Started, but not finished: My Winnipeg (2007), in which my fledgling interest in Canadian cinema came to a sad end.

Watched, but not remembered: The Best Years of Our Lives (1946); All About Eve (1950); The Assassin (2015).

Watched again: The Princess Bride (1987); When Harry Met Sally… (1989); The New World (2005).

Film rescued by a single scene: Paris, Texas (1984).

Film rescued by a single character: Cool Hand Luke (1967).

Disappointments: A Brighter Summer Day (1991), A Fish Called Wanda (1988).

Shortest films: Simon of the Desert (1965) [45m]; Steamboat Bill, Jr (1928) [1h10m]; Le Monde vivant (2003) [1h10m]

Longest films: A Brighter Summer Day (1991) [3h57m]; Ex Libris (2017) [3h25m]; Spartacus (1960) [3h17m].

Oldest films: The Great White Silence (1924); Steamboat Bill, Jr (1928); Pandora’s Box (1929).

Newest films: The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (Nov); Mission Impossible: Fallout (July); A Quiet Place (April).

January 7, 2019 at 8:01 am

I really want to see Personal Shopper!

January 7, 2019 at 2:09 pm

It is a really interesting movie. I hope you’ll have an opportunity to see it.

January 8, 2019 at 7:29 am

I’ll make some time 🙂

January 7, 2019 at 1:37 pm

Sounds like you haven’t watched “Roma” yet. Give it a try!

January 7, 2019 at 2:10 pm

That is correct, although it is near the front of my queue. It is nice that some of these high quality films are coming to Netflix right away.

January 8, 2019 at 11:43 am

Really nice assortment of films. It was a good year for cinema. I had a hard time narrowing my Top 10 list down. Check it out and let me know what you think.

Funny you mention Tree of Life. It was my favorite film from that year. But I got the extended edition for Christmas and actually popped it in last night. Didn’t get far into it but WOW! Still exquisite.

January 8, 2019 at 4:23 pm

Thanks for reading, Keith. I’ve seen only half of the films on your list, but most of the other half are on my “to watch” list. I didn’t like MI: Fallout as much as you, though I did think it was quite good. I’ve never heard of The Guardians!

As you’ll have gathered from my list, I don’t get to the theatre very often, so I tend to be a year or two (or fifty) behind.

January 8, 2019 at 4:25 pm

Oh you’re not alone. Unfortunately I haven’t heard from anyone else who has seen “The Guardians”. It’s sooo good.

January 18, 2019 at 5:59 am

Thanks for the reviews. After reflection and reading various theories, I think the ending to First Reformed is brilliant. It leaves the viewer to choose between hope and despair, a central question thoughout the film. Schrader doesn’t answer it for us. I would explain more but I don’t want spoil it for those who haven’t seen it.

Those of us in the old protestant mainline will easily get some of the nuances and problems in this film, e.g., mainline decline vs megachurch success. I wouldn’t want to make too much of a churchy discussion as the film’s themes are universal in scope. But the film does require some religious and historical literacy and those who have it will benefit.

January 22, 2019 at 12:54 pm

Yes, there is a question hanging in the air as to whether the dramatic conclusion is Toller’s salvation or damnation. I lean toward the former myself.

I thought the portrait of the mega-church and its pastor was one of the best parts of the movie. Yes, the comment about it being “more of a business than a church” has something to it, but at the same time the people involved are good-hearted and sincere.

I hope you don’t see too much of yourself in Rev Toller!

January 24, 2019 at 1:43 pm

A very interesting list, as always. There are several here that I’ve heard good things about in addition to your recommendations and will try to see.

I saw Umbrellas some years ago, perhaps twenty. Pre-Netflix, I’m pretty sure. I liked it a lot and have considered watching it again, but the memory of that heartbreak you mention has held me back. Also I do not have a jazz allergy.

I love film noir and Out of the Past is so far my favorite.

Your “greatest wonder” in Wonder Woman is one of the biggest reasons for my indifference to superhero movies.

January 24, 2019 at 2:22 pm

I do have a jazz allergy, quite sensitive. I have to carry two epipens, which I use to plug my ears.

Out of the Past took me by surprise, as I don’t think it’s one of the “great noirs” one usually hears about? But it must have been on some list or other because I can’t think how else I’d have put it on my to-watch list.

January 26, 2019 at 1:35 pm

It’s possible that I’m responsible for your having picked Out of the Past. I raved about it on my blog a while back, at least a year ago I’m sure. May have been in the 52 Movies series. I’m not sure how it came to my attention in the first place but I think I have seen it mentioned as one of the greats.

January 26, 2019 at 11:02 pm

Mac, yes, that is very possible!

February 4, 2019 at 11:50 am

I found A Quiet Passion disappointing, having loved both Dickinson and some other Davies – maybe my expectations were just too high. But I highly recommend his first two feature films, The Long Day Closes and Distant Voices, Still Lives.

I didn’t finish My Winnipeg myself, but I do think some of Maddin’s other films are worth seeing – both Careful and The Saddest Music in The World are bizarre yet wonderful.

February 6, 2019 at 9:48 pm

As I mentioned, this was my introduction to Davies, and I had no particular expectations going in. I’ve since watched Distant Voices, Still Lives, and I agree that it is something special.

I believe Roger Ebert named My Winnipeg on one of his “best of the year” lists, which is probably how it got onto my list of films to watch. Nobody’s perfect, God rest his soul.